We all know by now that Dragon Ball Kai was produced as a high-definition presentation to honor the 20th anniversary of Dragon Ball Z, but how exactly did it come to be? In this feature we will examine what motivated Toei Animation to make the decision to bring Dragon Ball into the digital age, and ultimately why the series was canceled after the Cell arc.

Throughout this feature we will be referring to publicly available fiscal year reports and presentations released by Toei Animation and Namco-Bandai on their corporate websites — we have tried to shorten up much of that discussion, but do suggest you read through it anyway for this feature to make more sense.

Financial Difficulties in the Industry

After a massive boom throughout the 2000s, it has been no surprise that the manga and anime industries have been struggling in recent years, especially with an international recession currently underway. Many companies have closed shop due to these financial difficulties, with their properties and licenses being sold to whomever will pay for them. Magazine and merchandise sales across the board have dropped and companies have had to become much more innovative in how they advertise and package their products.

Not only has the recession hurt many companies, but most anime fans have had less disposable income as well. This has led to fans doing anything from dropping magazine subscriptions, to being very selective in what anime DVDs they’ll buy, to not buying anything at all.

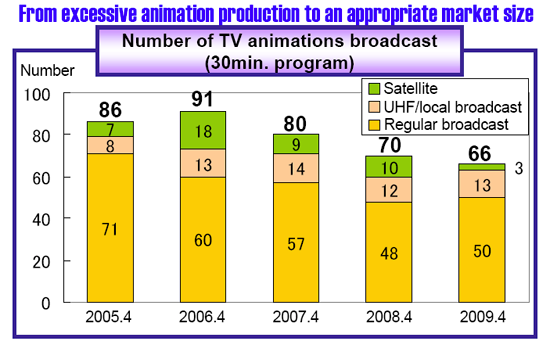

To counter this, the production of more anime series has actually slowed down. At its peak in Fiscal 2006, there were 91 different anime series being shown on TV in Japan. By Fiscal 2009 this number had significantly dropped down to 66 anime series. In their Fiscal 2009 report, Toei Animation noted that they had gone from an “excessive animation production to an appropriate market size.”

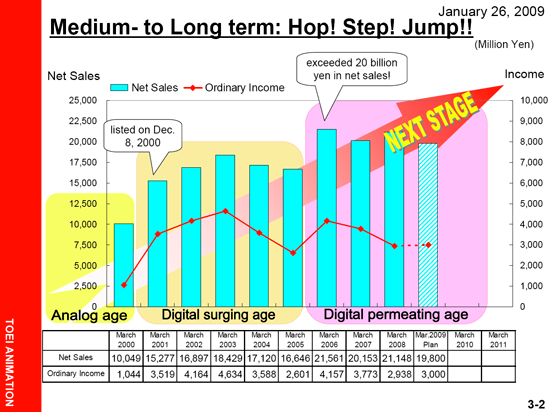

In their Q3 Fiscal 2009 (mid-2008) report, Toei Animation detailed a significant drop in net income, from 1.5 billion yen to a mere 174 million yen. The company quickly revised their forecast for the remainder of Fiscal 2009. Fortunately, the previous years had been financially friendly for Toei Animation, allowing them to maintain their viability as a leading animation company. However, what would Toei Animation do to reverse this situation and ensure continual growth?

Toei Animation’s Vision for Growth

Like any major company, Toei Animation not only develops a plan for current annual (short term) growth, but also a plan for sustainable future (long term) growth. As part of this future growth plan, Toei Animation highlighted in its Q3 Fiscal 2009 (April 2008 to December 2008) report that it had been keeping track of the transition from the analog age to the digital age, noting that March 2009 was well enough into the “Digital Permeating Age” that they could move on to the “Next Stage”.

This next stage featured a list of main objectives in how the company could reach its future growth goals. For now we will just note the specific ones related to this discussion:

TV Animation

- The largest animation market, our most important business.

- Constantly maintain four to six stable broadcasting time slots.

Collaboration

- Production of titles targeted for worldwide distribution.

- Enhance collaboration with overseas media.

Animation Library

- Use actively as assets.

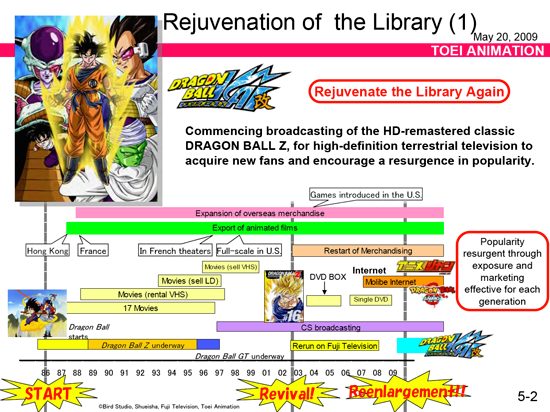

From all this we can really get a glimpse of where the idea of Dragon Ball Kai came from. Toei Animation wanted to do something with a TV anime, as it was their largest and most important market; they wanted it to be an anime that could have a worldwide distribution; and finally, something that would not be “new”, but rather something pre-existing from their massive animation library. In Toei Animation’s own words, they wanted to “rejuvenate the library again”, citing they currently have over 10,000 episodes and movies at their disposal. However, it was not specifically noted that Dragon Ball had been chosen as their “revitalization” series.

The Dragon Ball Kai series was finally announced in the Fiscal 2010 presentation, but with one slight addition to the criteria of why they had decided to go with their flagship property, Dragon Ball: its attractiveness to various generations. As with many countries around the world, Japan is currently experiencing lower birthrates due to the economic slowdown. With the number of children within this current generation decreasing, Toei Animation felt it needed to establish a solid, continual fanbase to achieve their sustainable growth goals. With the older fanbase of Dragon Ball already established throughout the world, they could simply add on to it and carry the Dragon Ball franchise far into the future, ultimately creating a consistent revenue source.

It was later announced that the series would be joining the One Piece anime in what Toei Animation and Fuji TV titled the “Dream 9” block. Toei Animation themselves even dubbed this the “back to back action time-slot”. The block pulled in significant TV ratings, giving Toei Animation a solid hour to show off two of their most touted franchises. In fact, Toei Animation attributed part of the increase in One Piece licensing sales to this new series collaboration, but that is another story for another time.

Their goal for Kai, as stated directly in the presentation, was to “broadcast the HD-remastered classic DRAGON BALL Z, for high-definition television to acquire new fans and encourage a resurgence in popularity”. When the series premiered in April 2009, 56.1% of males between the ages of 20-34 and 25.0% of males between the ages of 35-49 were watching Kai, but more importantly, 57.9% of all children in Japan between the ages of 4-12 were watching Kai. Toei Animation even went so far as to map out the course of Dragon Ball‘s history in Japan, including its revival in 2002 and their hopes of revitalizing the series.

In their Q2 Fiscal 2010 report, Toei Animation examined their plan for Dragon Ball Kai, stating:

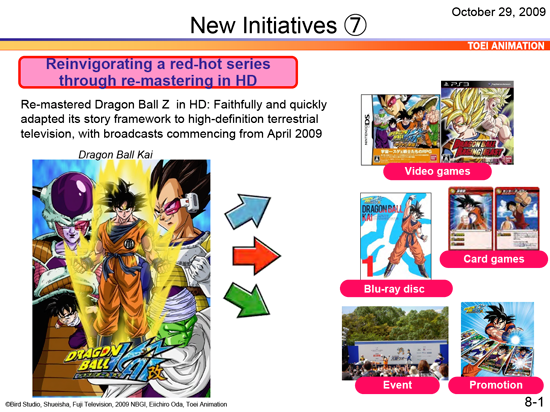

Re-mastered Dragon Ball Z in HD: Faithfully and quickly adapted its story framework to high-definition terrestrial television, with broadcasts commencing from April 2009.

It is quite interesting they would use of the word “quick” in reference to their high definition adaptation of the series, as many fans and critics of the series have often commented that there seems to be very little effort put into its production. From there the report went on to highlight other aspects of the series, such as promotional items, events, card games, video games, and Blu-ray discs.

As part of their goals, Toei Animation was also concerned with marketing the series overseas, specifically noting that Dragon Ball was an “evergreen brand” (essentially a “perennial” brand, as it does not have to be “replanted” or “restarted” every time in order for it to grow), as it has stood the test of time. Their stated international goal was “to strengthen the global licensing in other countries, to sustain and to expand the brand”. Shortly after the premiere of Kai in Japan, it was announced that FUNimation had licensed the series for distribution in North America under the title Dragon Ball Z Kai. Many other countries followed suit, rejuvenating the Dragon Ball series not just domestically in Japan, but globally.

Back in Japan, it slowly started to become clear that things were not as great as they had once appeared. From the beginning, based on Toei Animation’s projected episode count, it appeared as though they were only planning Kai as far ahead as whatever the current arc was. With dwindling sales numbers, and voice actors confirming they were not being hired to reprise their main roles as Toei Animation did not have the budget to afford their rates, the fate of Kai seemed to hang in the air for quite some time. Finally, in early March 2011, it was revealed that Kai would indeed be coming to end that month following the conclusion of the Cell arc. So the series was coming to an end, but why?

Did Dragon Ball Kai Fail to Deliver?

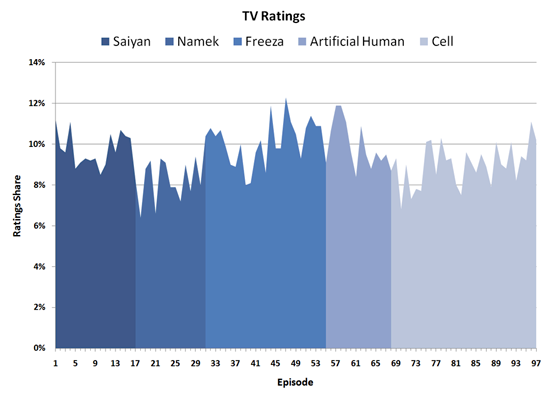

For all intents and purposes, we are not completely sure we can say Dragon Ball Kai was an actual “failure”, at least not in the same way we can say Dragon Ball GT was an absolute failure. For one thing, throughout the course of its run on Fuji TV, Dragon Ball Kai maintained consistent TV ratings and always ranked among the “Top 10” rated anime series. The series averaged a ratings share of 9.4%, peaking at 12.3% in the middle of the series (episode 47) and hitting a low of 6.4% at the beginning of the Namek arc (episode 18).

We can also assume that by the time the Cell arc ended, Toei Animation had already met one of its lofty goals for the series: acquiring new fans. The TV ratings indicate they had in fact acquired new fans, and more importantly, younger fans that might someday invest in the series for nostalgia reasons as they become older (similar to all of the series’ original fans that paid thousands of dollars for collector edition DVD box sets in the mid-2000s). However, it does not appear that the other part of their goal was ever quite met: a resurgence in the series’ popularity.

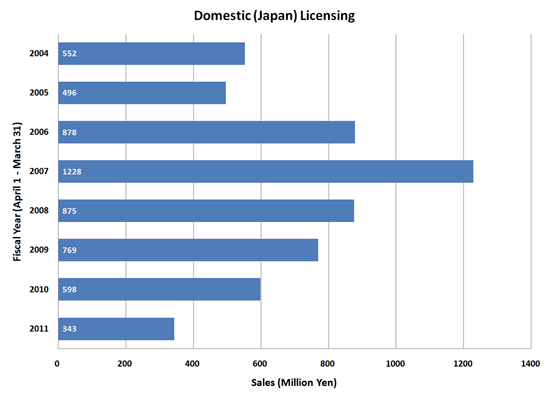

Based on the fiscal reports released by Toei Animation, Dragon Ball licensing sales and renewed popularity had peaked in Japan during Fiscal 2007 (shown below), just prior to Kai premiering early on in Fiscal 2010 (5 April 2009). By the end of Fiscal 2011 (31 March 2011), Dragon Ball-related sales in Japan had reached an all time low within the given data.

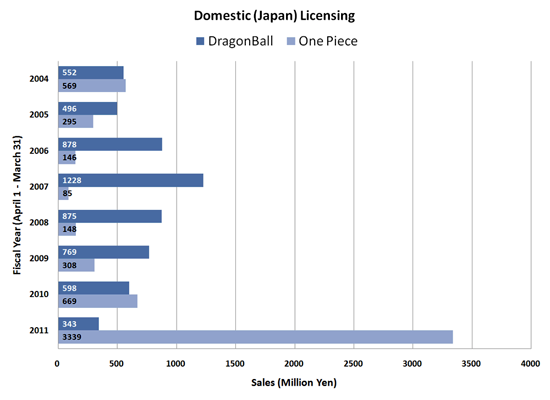

To help gauge the significance of these sales, let us compare the sales numbers of Dragon Ball with those of the leading anime, One Piece. At the point of Kai‘s cancellation in Fiscal 2011, One Piece was booming in comparison to the waning sales of Dragon Ball in Japan. While Dragon Ball pulled in a mere 343 million yen, Toei Animation saw an astounding 3.34 billion yen in sales revenue from One Piece during Fiscal 2011. In their Q3 Fiscal 2011 report, Toei Animation noted this had far and away exceeded all of their expectations, calling it a “boom” for the series. In addition, both of the Japanese media sales ranking companies SoundScan Japan and Oricon released reports showing that the Dragon Ball Kai Blu-rays rarely made their “Top 20” ranks. Even when they did, they usually only managed to rank 17-20, and quickly dropped off the charts following the week of their release.

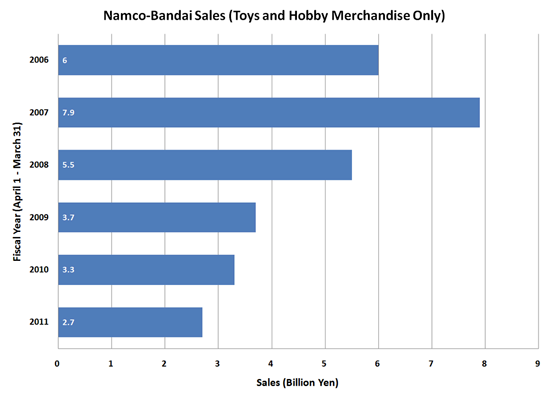

Not only were Dragon Ball sales declining for Toei Animation, but Namco-Bandai, the company responsible for all merchandise for the franchise, had also been reporting declining sales that mirror Toei Animation’s own trends.

Toys and hobby merchandise for the franchise (which does not include video games, reported separately) jumped slightly from 6.0 billion yen in Fiscal 2006 to 7.9 billion yen in Fiscal 2007 – a height that mirrors Toei Animation’s own peak for the franchise that same year. Each subsequent year, however, has seen a massive decline. In their Fiscal 2011 report, Namco-Bandai reported a total of only 2.7 billion yen for the franchise that fiscal year.

When you include video games in the mix, the franchise has taken a 5 billion yen drop for Namco-Bandai over the last two years, and in their Q3 Fiscal 2011 financial highlights report, was not even listed as a top-performing franchise, the first instance of this in quite some time.

This was not always the case, however. The PlayStation 2 generation and the Dragon Ball franchise treated Namco-Bandai quite well, but they were not able to carry forward that moderate success. A combination of oversaturation and diminishing quality in development has been called out by fans, and even hinted at by the company, themselves.

In Fiscal 2005, Bandai (at that point not yet merged with Namco) noted:

In Japan, while new types of mobile game consoles were released one after another and competition in the software market escalated, the “Dragon Ball Z 3” performed very well as the successor of the previous version.

In France, the United Kingdom, Spain and other European regions, the “Power Rangers” series – particularly, figures – showed quite strong movement. Also, new products from “Strawberry Shortcake”, “Tamagotchi Connexion”, “Pokémon”, “Thunderbirds”, etc. became popular. In addition, in the video game software area, the “Dragon Ball Z 3” contributed substantially to operating results.

For a couple years, this success carried forward, with specific nods to Europe time and time again. Contrast this, however, with just a year later when the company was already beginning to note:

In the Home Video game software, sales of Tamagotchi Connection: Corner Shop for the Nintendo DS shot past the one million mark in Japan. Super Robot Wars (alpha) 3, Tales of the Abyss, and Dragon Ball Z Sparking! (all for the PlayStation 2), also proved popular in the Japanese market. However, the market was depressed as a whole, and the Company was unable to respond swiftly to changing customer preferences, both in Japan and abroad. Furthermore, sales of other major game titles were slow. As a result, the business as a whole performed poorly, with the Company recording valuation losses on inventory assets.

Dragon Ball games would continue to be mentioned less and less until Fiscal 2010, when the franchise received no special nods at all – the exact time period during the shift to the Raging Blast franchise on the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360, itself coming with additional development costs.

Fans often point to 2008’s first “next-generation” outing for the franchise, Burst Limit, as possibly being a “failure” due to its lack of a sequel. Relative to other franchises, perhaps, but not relative to Dragon Ball, necessarily. Speaking specifically to the European market, the company noted in 2009 that:

In the Game Contents Business, Soul Calibur IV, developed for the PLAYSTATION 3 and the Xbox360, and Dragon Ball Z: Burst Limit, also for the PLAYSTATION 3 and the Xbox360, and others delivered strong performance.

This was the “beginning of the end”, so to speak, however. Sales of Burst Limit in Japan hit 92,000 copies on the PS3 as the number-one selling game its first week (with the Xbox 360 version down at number twelve). Two years later, Raging Blast 2 sold half that amount its first week. The same could be seen on the portable front: Dragon Ball DS 2 in 2010 sold about a quarter of what its predecessor did its first week in 2008, and while this year’s Ultimate Butōden managed to push just over 31,000 copies its first week, it is still a shadow of what has been achieved in the past.

What makes these trends all the more interesting is their relation to Dragon Ball Kai: a revival of the franchise on television did not carry over to an increase in sales of either video games or merchandise.

It is quite evident that many fans were simply enjoying the free HD broadcasts of the series while not buying any of its merchandise. Unfortunately, no show can survive in Japan without decent merchandise sales, which ultimately funds the show’s production. In almost every fiscal presentation during the course of Dragon Ball Kai‘s run, Toei Animation would note the “strong performance of character merchandise, DVDs/Blu-rays of One Piece and Pretty Cure“. Not once was Dragon Ball ever mentioned in a similar fashion.

This truly became evident in Q2 Fiscal 2011 when Toei Animation noted in its presentation that “under [a] continuous severe business environment, our goal is to aim to create [the] ‘next hit title’ by securing stable income from the multi-use of the current TV lineups and library titles”. In the same presentation, they noted a need to “strengthen the lineup” and even went so far as to say a “new TV lineup was in preparation for the 2011 year”. It was most likely at this point that Toei Animation had fully decided to move on from Dragon Ball Kai. Presumably using the profits from One Piece and Pretty Cure, they began the process of turning the popular manga series Toriko into their “next hit anime title” and giving it Dragon Ball Kai‘s time slot.

Conclusion

At the moment, it appears that the second wave of Dragon Ball has officially run its course in Japan, but that does not mean it will never return to the land of the rising sun again. Dragon Ball is a staple, not only to the country, but to Toei Animation as well. Unfortunately, many fans’ emotions blind them to the fact that anime is a business, and this time around, Dragon Ball did not make the cut. Toei Animation took a risk by simply re-mastering old footage rather than creating something entirely new, and with no reward to that risk, they had to stop the bleeding.

Will Dragon Ball be back? Undoubtedly it will at some point in the future. For now, we just have to remember that we lived through the first revival of Dragon Ball, in a time when you could actually watch the show live in Japan. If anything, the series has now fully been propelled into the digital age, leaving its mark on future generations of fans.