The Dragon Ball franchise has seen numerous animation supervisors and animators throughout its run, all with their own unique artistic style and approach that has shaped the appearance of the animation. This catalog provides a listing of the animation studios and supervisors involved with the various television series, with a profile page for each studio, in addition to a detailed look at the role and influence the animation supervisor has on the overall look of an episode and the general use of animation studios. For more information related to Toei Animation’s general animation process and roles of the other production staff, please visit the appropriate pages provided in the production section of this guide.

It should be noted that due to the artistic nature of this section, some personal artistic opinions will be necessary to evaluate and examine a given animator’s artistic style. While the artistic opinions presented may not match your own, it should be clear that a great effort has been placed on avoiding the use of personal opinion as much as reasonably possible. Any such statements of opinion will be noted accordingly and supporting information will be incorporated when available.

Glossary of Terms

Several animation production terms are used throughout this page and its various subsections to discuss the various roles and processes involved with the production of an animated series. These terms are defined below for reference:

- Key Frame: a single drawing that defines a transition or point of movement within animation. A cut or scene can be comprised of a varying number of key frames depending on the amount of motion being depicted.

- Cut: a single, continuous (unedited) shot between edits. As a cut is not defined by a specific length of time, but rather its continuity, it can be as short as a single frame (if it is a static shot) or several minutes long.

- Scene: a segment or division of an episode that takes place at a certain place and time in the story. A scene can be comprised of only a single cut, or by several cuts edited together in sequential order. A scene change is typically identified by a transition to a different location.

The Role of Animation Supervisor

The animation supervisor is the first layer of quality control for an episode and is responsible for overseeing, checking, and correcting the key animator’s layouts and drawings. They oversee every aspect of the key animation process, and ultimately the final look of the animation hinges on their artistic ability. After the layouts for a key animator’s assigned cuts have been corrected and approved, they begin drawing the episode’s key art based on these layouts. As the key art for a given cut is completed, it is sent to the animation supervisor for review.

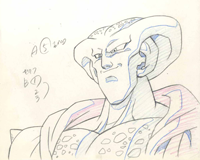

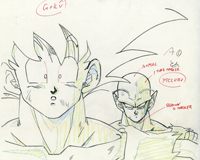

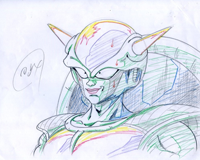

If a cut’s key art diverges too far from the episode’s overall style, does not appear to be inline with the character designs, or for any other reason, the animation supervisor will revise the drawings and add corrective notes. This is done by placing a sheet of translucent paper (typically yellow) over each key frame and marking up portions with needed corrections, although in some cases when necessary the animation supervisor will redraw the entire frame or cut. However, it is also possible that the animation supervisor will provide no corrections, and approve the key art as-is. Provided below are examples of various animation supervisor corrections, which range from slight corrections (Redict’s eye) to complete redraws (Freeza).

(Dragon Ball GT Episode 5)

(Dragon Ball Z Episode 95)

(Dragon Ball Z Episode 62)

As the in-between frames will be based on the key art, they also take on the look of the animation supervisor’s corrections. Once all of the frames from a cut or scene have been corrected or approved, the in-between animation process begins. Beyond this point the look and style of the episode is set, as the key animators and animation supervisors have no further involvement in an episode’s production.

Just as with key animators, each animation supervisor is different, particularly with their corrections. Some animation supervisors will heavily edit key art to make an episode as cohesive as possible, while others will only provide minor corrections and let the key animator’s individuality more predominately show through. There are also instances where the production schedule does not allow the animation supervisor enough time to sufficiently make the necessary corrections — which is especially prevalent when a production outsources much of its animation — and uncorrected cuts make their way into the final broadcast episode. In some of these instances, the uncorrected cuts are later replaced with corrected footage in the home video release. On occasion the animation supervisor will also provide a few cuts or scenes in order to help meet the production deadline, but there are also those that simply prefer to provide the key art for an entire episode by themselves.

As with many key positions, the role of the animation supervisor has changed over the years as common production processes have shifted toward the use of more digital production methods with constrained production schedules. Due to these shortened schedules, the use of multiple animation supervisors is often required to complete the animation for a given episode. To counteract the use of multiple supervisors, a “Chief Animation Supervisor” has become common to provide an additional layer of quality control. As each animation supervisor is overseeing only a specific section of the episode’s production, the chief animation supervisor fills the role of overseeing the entire episode’s production and provides additional corrections to those already provided by a section’s animation supervisor. However, the corrections from the chief animation supervisor are often minor in comparison, and therefore a section’s overall look is still heavily dictated by the corrections provided by the animation supervision.

The Use of Animation Studios

At the time of Dragon Ball’s original syndicated run, Toei Animation lacked the number of in-house animators required to produce the significant number of animated series they were producing. Therefore, Toei Animation would often subcontract various outside studios in these instances to produce the bulk of the animation for their TV series and supplement them with their own in-house animators as needed. This type of multi-studio production process was used to produce the three original Dragon Ball TV series. The subcontracted animation studios provided their own animation supervisors and key animators, who for the most part worked only on episodes being animated by their specific studio. On occasion animators from Toei Animation would fill in to assist an episode’s key animators, but it would not be until partway through Dragon Ball Z that any animation supervisor from Toei Animation would step in to actually supervise an episode.

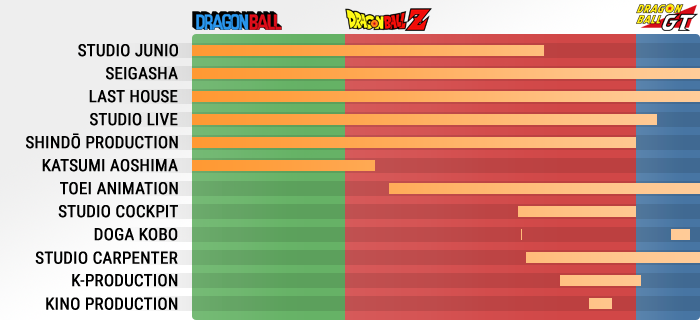

Following the departure of Studio Junio, Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru of Toei Animation officially took over the roles of chief animator and character designer in episode 200 of the Dragon Ball Z TV series, both of which had been held up to that point by Minoru Maeda of Studio Junio. At the same time Tadayoshi Yamamuro assumed the same roles for the series’ movie productions. It was also at this point that Toei Animation began subcontracting some additional animation studios, such as Studio Cockpit, Doga Kobo, Studio Carpenter, K-Production, and Kino Production, to assist in the series’ production. The chart below illustrates the involvement of each subcontracted animation studio, which are further broken down by animation supervisor in the following section.

In contrast to this, the production of Dragon Ball Super was largely handled in-house by Toei Animation, using a combination of their own animation staff, animators from Toei Animation Philippines, and a few subcontracted studios as needed. A more detailed discussion of the series’ production is provided in the section below.

Supervisor Catalog

The catalog is organized by series and then further by studio, along with each supervisor’s general series involvement. Supervisors listed with a blue corner tab are linked to a detailed studio profile page with additional information, such as detailed biographical notes, discussion of each supervisor’s artistic style, corrections, and animation abilities, a breakdown of their animation teams and their notable animation cuts, and much more. While this catalog does list all of the animation supervisors credited, it should be noted that some of the supervisors listed with very few episode credits to their name were either key animators filling in for their studio’s regular supervisor(s) or a supervisor from Toei Animation stepping in to help cover an episode.

Note that the images shown below are not necessarily drawn by that respective animation supervisor, but rather are taken from episodes under their supervision.

With the production of Toei Animation’s Dr. Slump – Arale-chan animated series coming to an end in February 1986, the majority of the series’ animation staff transitioned directly into production of the company’s next animated adaptation, Dragon Ball. The series featured six main animation supervisors from the animation studios subcontracted by Toei Animation at the time. All six supervisors remained on staff for the duration of the series’ syndicated run and would continue on into the production of Dragon Ball Z. While much of their staff consisted of animators from their own studios, numerous Toei Animation animators regularly worked with specific studios. In terms of consistency, the general overall animation throughout the series remained rather uniform, due in large part to its consistent scheduling and studio rotation. The rounder character designs at the time were also well suited to the majority of the supervisor’s artistic styles, and having already worked together on Akira Toriyama’s previous series, the animation staff was well acquainted with the author’s drawing style.

前田 実Minoru MaedaStudio Junio

前田 実Minoru MaedaStudio Junio

Episodes 1-153 (23) 竹内留吉Tomekichi TakeuchiSeigasha

竹内留吉Tomekichi TakeuchiSeigasha

Episodes 1-153 (23) 内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

Episodes 1-153 (44) 小原太一郎Tai’ichirō OharaLast House

小原太一郎Tai’ichirō OharaLast House

Episodes 76-98 (3) 海老沢幸男Yukio EbisawaStudio Live

海老沢幸男Yukio EbisawaStudio Live

Episodes 1-153 (22) 進藤満尾Mitsuo ShindōShindō Production

進藤満尾Mitsuo ShindōShindō Production

Episodes 1-153 (23) 青嶋克己Katsumi AoshimaUnaffiliated

青嶋克己Katsumi AoshimaUnaffiliated

Episodes 1-153 (15)

Although the TV series title had changed, the animation staff and supervisors remained virtually the same up through the beginning portions of the series as they had been in Dragon Ball. However, as the series progressed beyond the initial story arc, a few animation studios began transitioning from their established supervisors to younger, talented animators. Seigasha was the first studio to do so, promoting Masahiro Shimanuki to take over supervisor responsibilities from Tomekichi Takeuchi, who would still remain on as a key animator through Dragon Ball GT. Kazuya Hisada later took over for Shimanuki at the end of the Freeza arc, and the two would alternate the role for large chunks of episodes throughout the remainder of the series. Similarly, Shindō Production would eventually promote Tadayoshi Yamamuro to animation supervisor to replace Mitsuo Shindō, who left the series following the Garlic Jr. arc.

With the series’ soaring popularity, Toei Animation began producing two Dragon Ball Z movies a year. Due to the tight production schedules of these movies, Katsumi Aoshima transitioned from his involvement with the TV series to working only on the series’ movies, where he remained until his departure following the series’ fifth movie. Similarly, Minoru Maeda’s involvement with the TV series became quite strained due to his heavy involvement with the near-constant production of movies. Other animators soon began filling in to supervise Maeda’s episodes in his absence, including Masaki Satō from Studio Junio and Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru, Takeo Ide, and Naoki Miyahara from Toei Animation, all of which regularly worked with Studio Junio. As the series hit the halfway point of the Cell arc, production was finished nearly simultaneously on both the series’ eighth movie and second TV special. Following this, Studio Junio left the series, although Minoru Maeda would continue to be credited as the series’ character designer and chief animator, likely in name only. Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru of Toei Animation officially took over the roles for the TV series in episode 200, while Shindō Production’s Tadayoshi Yamamuro assumed the same roles for the series’ movie productions.

Following Studio Junio’s departure, Toei Animation subcontracted Studio Cockpit and Studio Carpenter to fill in the gaps left in the studio rotation schedule, with both studios remaining regulars in the rotation for the remainder of the series. Animation studio Doga Kobo, who had been subcontracted by Toei Animation to assist with in-between animation work on the series, was also used on occasion to supplement the key animation staff. Still seeing the need for an additional studio to cover episodes as the series entered the Majin Boo arc, due to the series’s movie productions having grown larger and pulling much of the TV animation staff away, Toei Animation subcontracted K-Production and inserted them into the regular studio rotation. As the series entered its final year of production, animation studio Kino Production would step in on occasion to supervise a handful of episodes as needed. Kino Production’s involvement appears to be a mere matter of convenience in order to maintain the series’ production schedule, as the studio was already subcontracted by Toei Animation and working on movies for the Dr. Slump – Arale-chan series at the time.

As the series came to an end in early-1996, seven contracted studios were regularly contributing animation, not including Toei Animation’s own animation staff. While the series began with a rather consistent animation style, it closed with a wide range of styles, some of which were quite unique to the series.

前田 実Minoru MaedaStudio Junio

前田 実Minoru MaedaStudio Junio

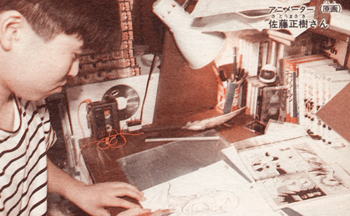

Episodes 1-164 (18) 佐藤正樹Masaki SatōStudio Junio

佐藤正樹Masaki SatōStudio Junio

Episode 64 (1) 竹内留吉Tomekichi TakeuchiSeigasha

竹内留吉Tomekichi TakeuchiSeigasha

Episodes 1-63 (11) 島貫正弘Masahiro ShimanukiSeigasha

島貫正弘Masahiro ShimanukiSeigasha

Episodes 68-225 (15) 久田和也Kazuya HisadaSeigasha

久田和也Kazuya HisadaSeigasha

Episodes 98-291 (16) 内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

Episodes 1-291 (71) 海老沢幸男Yukio EbisawaStudio Live

海老沢幸男Yukio EbisawaStudio Live

Episodes 1-291 (53) 進藤満尾Mitsuo ShindōShindō Production

進藤満尾Mitsuo ShindōShindō Production

Episodes 1-116 (22) 山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroShindō Production

山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroShindō Production

Episodes 122-291 (19) 青嶋克己Katsumi AoshimaUnaffiliated

青嶋克己Katsumi AoshimaUnaffiliated

Episodes 1-30 (5) 中鶴勝祥Katsuyoshi NakatsuruToei Animation

中鶴勝祥Katsuyoshi NakatsuruToei Animation

Episodes 44-120 (2) 井手武生Takeo IdeToei Animation

井手武生Takeo IdeToei Animation

Episodes 129-138 (2) 宮原直樹Naoki MiyaharaToei Animation

宮原直樹Naoki MiyaharaToei Animation

Episodes 159-291 (4) 増永計介Keisuke MasunagaStudio Cockpit

増永計介Keisuke MasunagaStudio Cockpit

Episodes 174-291 (18) 服部一郎Ichirō HattoriDoga Kobo

服部一郎Ichirō HattoriDoga Kobo

Episode 177 (1) 袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaStudio Carpenter

袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaStudio Carpenter

Episodes 182-291 (16) 石川晋吾Shingo IshikawaK-Production

石川晋吾Shingo IshikawaK-Production

Episodes 216-291 (13) 林 委千夫Ichio HayashiKino Production

林 委千夫Ichio HayashiKino Production

Episode 245 (1) 北條直明Naoaki HōjōKino Production

北條直明Naoaki HōjōKino Production

Episodes 252-267 (3)

Following the success and popularity of the Dragon Ball Z TV series, Toei Animation decided to extend the franchise beyond just the scope of the original manga and immediately began production on its successor, Dragon Ball GT. The main staple of animation studios were retained for the new series’ production with only a few minor changes in staff — Toshiyuki Kan’no was promoted to animation supervisor for Studio Live, Noboru Koizumi was promoted for Doga Kobo, and Tadayoshi Yamamuro left Shindō Production to join Toei Animation. Both K-Production and Doga Kobo were retained as subcontracted studios to supervise the animation of a handful of episodes, while Shindō Production, Studio Cockpit, and Kino Production all left to work on other series. This also marks the first main instance of the talented animators at Toei Animation stepping up to supervise a significant portion of a Dragon Ball series, whereas previously they had merely fulfilled a more supportive role.

Toei Animation’s Naoki Miyahara was appointed as the series’ Chief Animation Supervisor and Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru remained the character designer. However with no movies slated for production, Tadayoshi Yamamuro returned to a regular TV series animation supervisor role, but would eventually take over as Chief Animation Supervisor for Miyahara halfway through the series in February 1997. From this point forward, Yamamuro became the predominate animation supervisor for every animated Dragon Ball production up through March 2018.

Throughout the series the animation staff and studios remained relatively unchanged, resulting in a rather consistently produced product. The most significant change of note came near the end of the series when EEI-TOEI (now Toei Animation Philippines) took over production of the series’ in-between animation. When the series ended in November 1997, Toei Animation had supervised and produced nearly a third of the episodes. The majority of the animation staff would remain together and transition into production of Toei Animation’s Doctor Slump, a remake of Akira Toriyama’s original hit series that immediately took over the Dragon Ball GT time slot on Fuji TV.

久田和也Kazuya HisadaSeigasha

久田和也Kazuya HisadaSeigasha

Episodes 1-64 (11) 内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

内山正幸Masayuki UchiyamaLast House

Episodes 1-64 (15) 袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaStudio Carpenter

袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaStudio Carpenter

Episodes 1-64 (9) 菅野利之Toshiyuki Kan’noStudio Live

菅野利之Toshiyuki Kan’noStudio Live

Episodes 1-21 (4) 石川晋吾Shingo IshikawaK-Production

石川晋吾Shingo IshikawaK-Production

Episode 5 (1) 山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroToei Animation

山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroToei Animation

Episodes 1-64 (9) 井手武生Takeo IdeToei Animation

井手武生Takeo IdeToei Animation

Episodes 1-64 (6) 稲上 晃Akira InagamiToei Animation

稲上 晃Akira InagamiToei Animation

Episodes 11-35 (3) 宮原直樹Naoki MiyaharaToei Animation

宮原直樹Naoki MiyaharaToei Animation

Episodes 1-64 (2) 小泉 昇Noboru KoizumiDoga Kobo

小泉 昇Noboru KoizumiDoga Kobo

Episodes 36-54 (4)

Debuting in July 2015 on the heels of the massive theatrical success of Resurrection ‘F’, Dragon Ball Super was the franchise’s first all-new TV series in 18 years. However, planning and development of the TV series was extremely limited from the onset and it was hastily rushed into production in order to fill the soon-to-be vacant timeslot of the second phase of Dragon Ball Kai. Similar to the preceding movies, the series’ story and characters were developed by original manga author Akira Toriyama. Tadayoshi Yamamuro, having just finished his work on Resurrection ‘F’, returned to be the series’ animation character designer and supervising director of animation. As with the production of Dragon Ball GT, the majority of the animation was supervised and produced in-house by Toei Animation, with Toei Animation Philippines handling most of the finishing work.

Due to the significantly rushed production schedule, especially early on in the series’ production, a consistent rotation of animators was never truly established as would normally be the case. The key animators working on a specific episode were often an inconsistent combination of scheduled animators from Toei Animation who regularly worked with a section’s animation supervisor, random animators from other Toei Animation teams and series that were available at the time, animators from Toei Animation Philippines, and outsourced or freelance animators. The stringent production schedule also forced Toei Animation to on occasion outsource entire sections of an episode to other foreign animation studios to help alleviate the workload on their internal staff.

To help reduce the affects of the limited production time, episodes partway into the series began being divided into two or three sections with each overseen by its own animation supervisor. In addition to this, Toei Animation also introduced several 2nd key animators to clean up the main key animators’ work prior to being reviewed and corrected by the animation supervisor. To maintain some semblance of consistency across each section, each episode was further overseen and corrected by one of the series’ chief animation supervisors, Takeo Ide or Miyako Tsuji, from Toei Animation. With these increased efforts the series’ production schedule eventually improved and the animation staff was able to settle into a more consistent rotation around the Future Trunks story arc, resulting in improved animation quality. These changes would last throughout the remainder of the series’ production.

北野幸広Yukihiro KitanoToei Animation

北野幸広Yukihiro KitanoToei Animation

Episodes 1-97 (18) 石川 修Osamu IshikawaToei Animation

石川 修Osamu IshikawaToei Animation

Episodes 2-128 (20) 八島善孝Yoshitaka YashimaToei Animation

八島善孝Yoshitaka YashimaToei Animation

Episodes 3-125 (20) 苫 政三Seizo TomaUnknown

苫 政三Seizo TomaUnknown

Episodes 4-55 (5) 舘 直樹Naoki TateToei Animation

舘 直樹Naoki TateToei Animation

Episodes 5-130 (17) 岡 辰也Tatsuya OkaUnknown

岡 辰也Tatsuya OkaUnknown

Episodes 6-27 (3) 眞部周一郎Shūichirō ManabeUnknown

眞部周一郎Shūichirō ManabeUnknown

Episodes 6-130 (16) 丸山大勝Hirokatsu MaruyamaUnknown

丸山大勝Hirokatsu MaruyamaUnknown

Episode 6 (1) 加野 晃Akira KanoUnknown

加野 晃Akira KanoUnknown

Episodes 8-32 (3) 島貫正弘Masahiro ShimanukiToei Animation

島貫正弘Masahiro ShimanukiToei Animation

Episodes 8-127 (20) 山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroToei Animation

山室直儀Tadayoshi YamamuroToei Animation

Episodes 13-131 (2) 小山和弘Kazuhiro KoyamaUnknown

小山和弘Kazuhiro KoyamaUnknown

Episodes 14-21 (2) 井関修一Shūichi IsekiUnknown

井関修一Shūichi IsekiUnknown

Episode 16 (1) 木下由衣Yui KinoshitaUnknown

木下由衣Yui KinoshitaUnknown

Episodes 17-88 (9) 成松義人Yoshito NarimatsuUnknown

成松義人Yoshito NarimatsuUnknown

Episode 25 (1) 田之上 慎Makoto TanoueUnknown

田之上 慎Makoto TanoueUnknown

Episode 25 (1) 小山一寛Kazuhiro KoyamaUnknown

小山一寛Kazuhiro KoyamaUnknown

Episode 27 (1) 唐澤雄一Yūichi KarasawaUnknown

唐澤雄一Yūichi KarasawaUnknown

Episodes 31-129 (11) フランシス・カネダFrancis CanedaToei Animation

フランシス・カネダFrancis CanedaToei Animation

Episode 31 (1) ノエル・アンニョヌエボNoel AñonuevoToei Animation

ノエル・アンニョヌエボNoel AñonuevoToei Animation

Episodes 31-124 (9) 篁 馨Kaoru TakamuraUnknown

篁 馨Kaoru TakamuraUnknown

Episodes 32-98 (8) 金 水湖Shui-hu JinUnknown

金 水湖Shui-hu JinUnknown

Episode 37 (1) 楠木智子Tomoko KusunokiUnknown

楠木智子Tomoko KusunokiUnknown

Episodes 38-88 (4) 松坂定俊Sadatoshi MatsuzakaUnknown

松坂定俊Sadatoshi MatsuzakaUnknown

Episode 43 (1) 大西陽一Yōichi ŌnishiToei Animation

大西陽一Yōichi ŌnishiToei Animation

Episodes 43-124 (6) 李 周鉉Joo-hyon LeeUnknown

李 周鉉Joo-hyon LeeUnknown

Episodes 45-53 (2) 直井正博Masahiro NaoiToei Animation

直井正博Masahiro NaoiToei Animation

Episode 48 (1) 信実節子Setsuko NobuzaneUnknown

信実節子Setsuko NobuzaneUnknown

Episode 50 (1) 大野 勉Tsutomu OnoUnknown

大野 勉Tsutomu OnoUnknown

Episodes 60-126 (10) 梨澤孝司Kōji NashizawaToei Animation

梨澤孝司Kōji NashizawaToei Animation

Episodes 62-129 (9) 板井寛幸Hiroyuki ItaiUnknown

板井寛幸Hiroyuki ItaiUnknown

Episodes 64-127 (11) ポール・アンニョヌエボPaul AñonuevoToei Animation

ポール・アンニョヌエボPaul AñonuevoToei Animation

Episodes 76-127 (9) 澤木巳登理Midori SawakiUnknown

澤木巳登理Midori SawakiUnknown

Episodes 79-119 (2) ジョーイ・カランギアンJoey CalangianToei Animation

ジョーイ・カランギアンJoey CalangianToei Animation

Episodes 81-124 (9) 仁井宏隆Hirotaka NiiUnknown

仁井宏隆Hirotaka NiiUnknown

Episodes 82-129 (7) ユージン・アイソンEugene AysonToei Animation

ユージン・アイソンEugene AysonToei Animation

Episodes 83-121 (6) 山崎秀樹Hideki YamazakiUnknown

山崎秀樹Hideki YamazakiUnknown

Episode 90 (1) 田中千皓Chihiro TanakaUnknown

田中千皓Chihiro TanakaUnknown

Episodes 95-120 (4) 生田目康裕Yasuhiro NamatameUnknown

生田目康裕Yasuhiro NamatameUnknown

Episodes 103-126 (4) 高橋優也Yūya TakahashiUnknown

高橋優也Yūya TakahashiUnknown

Episodes 114-122 (2) 山内尚樹Naoki YamauchiUnknown

山内尚樹Naoki YamauchiUnknown

Episode 119 (1) 袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaToei Animation

袴田裕二Yūji HakamadaToei Animation

Episodes 121-128 (2)